C. S. Lewis: Difference between revisions

1d4chan>Zimriel |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Fun fact: the Space Trilogy makes reference to what would have been the Time Travel trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien, except we never got anything more than unfinished manuscripts. Basically it would have been Tolkien's way of tying in the history of the Lord of the Rings with the known history and medieval legends of today's world. The closest thing we get is ''[[The Silmarillion]]''. | Fun fact: the Space Trilogy makes reference to what would have been the Time Travel trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien, except we never got anything more than unfinished manuscripts. Basically it would have been Tolkien's way of tying in the history of the Lord of the Rings with the known history and medieval legends of today's world. The closest thing we get is ''[[The Silmarillion]]''. | ||

Also of note are Lewis' books about the afterlife, as they | Also of note are Lewis' books about the afterlife, as they were unique... at the time. ''The Screwtape Letters'', for example, is a fictional series of letters written by a demon, Screwtape, to his nephew Wormwood, giving him advice on seducing a man to the ways of [[Heresy|sin]] and [[Chaos|damnation]]. [[Warp|Hell]] isn't depicted as a brutal prison as in Dante's Inferno, but more like a [[Administratum|diabolical bureaucracy]]; where [[Dark Eldar|demons consume human souls as we would consume wine]], and the more evil they are, the finer their vintage. Screwtape gives excellent advice on how to manipulate good intentions into bad deeds, and the book's unusual point of view lends itself to some creative ideas. In particular, the subplot where Wormwood and Screwtape subtly try to undermine the other by reporting them to Hell's [[Inquisition]] while maintaining correspondence is quite entertaining. Suffice to say, it's an excellent read for [[GM|GMs]] wishing to run a particularly [[Tzeentch|cunning or manipulative]] demon. | ||

==Legacy== | |||

Unfortunately for Lewis, American Protestant evangelicals are fans. | |||

Randy Alcorn (for one) has "updated" ''Screwtape'' to rail against modern evils ... like [[Dungeons & Dragons]]. American evangelicals are also fond of Lewis' well-poisoning "argument" that Jesus was either insane, a liar, or the Lord - they call this the "trilemma". But hey, at least the evangelicals have totally been winning allies with this stuff, as witness their string of victories in "the culture war" there. | |||

== See Also == | == See Also == | ||

Revision as of 16:05, 17 June 2020

Clive Staples Lewis (better known as "C. S."), not to be confused with C.S. Goto (how dare you confuse the two), nor with Lewis Carroll, was J. R. R. Tolkien's good friend and another influential early modern fantasy writer. He was also an essayist and a theologian, one of the best of the last century, writing on subjects such as the relationship between science and religion in the modern age, the nature of the afterlife, and arguing that the existence of aliens wouldn't clash with Christian beliefs. Almost all of Lewis' works tend to come across as astoundingly well-thought out; many of his more devoted fans would argue that reading his work is like reading the Necronomicon, except it increases your sanity.

His Fictional Works

- The Space Trilogy

- Out of the Silent Planet (1938)

- Perelandra (1972) (C.S Lewis' favorite book by his own admission)

- That Hideous Strength (1974) (AKA That Hideous Book, according to JRR Tolkien).

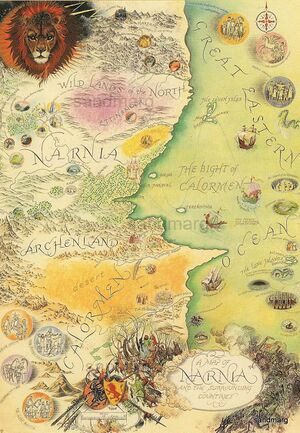

- The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956)

- The Magician's Nephew (actually written after The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, but its events take place first)

- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

- The Horse and His Boy

- Prince Caspian

- The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

- The Silver Chair

- The Last Battle

- The Screwtape Letters

- The Pilgrim's Regress

- The Great Divorce

- Till We Have Faces

Why He Was Influential

With the Narnia series, C. S. Lewis brought to the table the "everything in mythology but the kitchen sink" approach to fantasy writing. Norse Mythology, Greco-Roman Mythology, Judeo-Christian Theology, even modern folklore like Santa Claus got worked in. It's to his everlasting credit that he threw all these things into a blender and came up with something really awesome (even Santa Claus). Basically, if Tolkien gave modern fantasy RPGs Halflings, Orcs and Dark Lords, Lewis gave it Centaurs, Minotaurs (and potentially non-evil ones at that), Merfolk, and talking animals. Narnia also included one of the earliest and most logically consistent examples of the "secret magical world parallel to our own" trope. And it is also an early form of the Isekai genre.

On His Writing

When compared to his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis was more of a philosopher and theologian than a world-builder. While Tolkien had beliefs and viewpoints which manifested in his writings, they usually came up as background details and a component of greater world building. Lewis, in contrast, wrote his works with the primary intent of arguing a point or presenting an idea rather than creating a fantasy world. This isn't to say that Lewis' writings have poor world-building, it just wasn't as much of a priority for him as having a clear and consistent theme. Although his writings tend to be far more overt with their religious message, it should be noted that they're not written in a judgemental fire-and-brimstone style, but more like a neutral-toned fable or philosophy lecture. The Narnia series might basically be about a fantasy land with lion Jesus and ice witch Satan, but it is generally more readable than The Lord of the Rings, as Lewis didn't feel the need to include songs on every other page, or detail the name and lineage of every single person who participated in each battle.

He is also known for The Space Trilogy, which is arguably the earliest example of Christian science fiction (a subgenre that exists but is almost unheard of in mainstream media). The first book (Out of the Silent Planet) is about a man named Ransom being kidnapped and taken to a planet (called Malacandra by its inhabitants, the one we call Mars) where he meets aliens, the angel in charge of Mars under God and learns more about the way the universe works and the situation of Earth. The second book (Perelandra) is about Ransom being taken to the planet Perelandra (the one we call Venus, which has a livable atmosphere due to Venus' actual deadly climate being unknown at the time) to stop a demon from recreating The Fall of Man with Venus' equivalent of Adam and Eve. In the third book (That Hideous Strength) the main characters Ransom and Mark have to work together against a scientific institute which is actually a front for sinister supernatural forces.

Fun fact: the Space Trilogy makes reference to what would have been the Time Travel trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien, except we never got anything more than unfinished manuscripts. Basically it would have been Tolkien's way of tying in the history of the Lord of the Rings with the known history and medieval legends of today's world. The closest thing we get is The Silmarillion.

Also of note are Lewis' books about the afterlife, as they were unique... at the time. The Screwtape Letters, for example, is a fictional series of letters written by a demon, Screwtape, to his nephew Wormwood, giving him advice on seducing a man to the ways of sin and damnation. Hell isn't depicted as a brutal prison as in Dante's Inferno, but more like a diabolical bureaucracy; where demons consume human souls as we would consume wine, and the more evil they are, the finer their vintage. Screwtape gives excellent advice on how to manipulate good intentions into bad deeds, and the book's unusual point of view lends itself to some creative ideas. In particular, the subplot where Wormwood and Screwtape subtly try to undermine the other by reporting them to Hell's Inquisition while maintaining correspondence is quite entertaining. Suffice to say, it's an excellent read for GMs wishing to run a particularly cunning or manipulative demon.

Legacy

Unfortunately for Lewis, American Protestant evangelicals are fans.

Randy Alcorn (for one) has "updated" Screwtape to rail against modern evils ... like Dungeons & Dragons. American evangelicals are also fond of Lewis' well-poisoning "argument" that Jesus was either insane, a liar, or the Lord - they call this the "trilemma". But hey, at least the evangelicals have totally been winning allies with this stuff, as witness their string of victories in "the culture war" there.

See Also

- CS Lewis Doodle, a YouTube channel which animates several of his essays and written works.